“I’m Mohammad Ali Keshavarz, the actor who plays the director. The other actors are all locals.”

-Opening lines of Through the Olive Trees (Abbas Kiarostami, 1994), spoken by Mohammad Ali Keshavarz.

“I'm playing the role of a little old lady, plump and talkative, telling her life story.”

-Opening lines of The Beaches of Agnès (Agnès Varda, 2008), spoken by Agnès Varda.

It would perhaps be easier to talk about the gulf that separates Abbas Kiarostami from Agnès Varda. The former, easily considered the greatest cinematic export from Iran’s New Wave, was more inspired by a handful of somber, grounded Italian neorealist films and the national poetic mythology of his native country than he was the burgeoning cross-artistic pollination that bred the French New Wave. Varda, for her part, was an iconoclast who spent the bulk of her last twenty years making DVD extras for her earlier films and multimedia installation pieces, including one where she dressed up as a walking, talking potato. No record of them ever meeting exists, though Varda did shoot in Kiarostami’s native country, the paratextual The Pleasure of Love in Iran (1976) which accompanied One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977), and Kiarostami’s late career masterpiece Certified Copy (2010) was shot at least partially in the French language. Varda’s penultimate film Faces Places (2017), the freewheeling travel documentary co-directed with photographer JR, was screened at the 70th Cannes Film Festival alongside Kiarostami’s final film 24 Frames (2017), but, alas, the Iranian master had already passed. This is the closest they ever got.

Ultimately, however, what connects these two giants is far greater than the superficialities of their geographical distance, namely a supremely gifted use of self-reflexivity heretofore unseen. Both shared a childlike curiosity with the digital camera revolution at the turn of the century that reinvigorated their once dormant careers, and both, on multiple occasions, espoused an overarching desire to deconstruct (and reconstruct) preconceived notions over accepted divisions between reality and fiction. In practice this meant a rash of formal ingenuity, mischievous casting choices and a consistent motif of memorific reinterpretation and recreation. Their shared history as photographers-cum-filmmakers who saw cinema as the inevitable culmination of all the material arts manifested in a persistent experimentation with new ways of storytelling both technologically and pedagogically. While Varda primarily used modalities of fiction storytelling in her complexly interwoven self-portrait documentaries, Kiarostami flipped the recipe such that documentary practice and openly autobiographical elements bled through into his fiction.

Varda’s use of herself in her cinema can be traced as early as her short film L’Opéra Mouffe (1958), an experimental documentary reflecting on her pregnancy with her first child, Rosalie. But Varda’s most structurally audacious film, one that challenges all established boundaries between documentary and fiction, is the oft-neglected Lions, Love… and Lies (1969). Made while Varda was in Los Angeles with her husband Jacques Demy, the aleatory fiction is ostensibly about a filmmaker (New York avant-garde staple Shirley Clarke, as herself) who decides to make a film about the hippie love triangle between Jim Rado, Jerry Ragni (creators of the musical Hair) and Andy Warhol’s muse Viva. The three lovers share each other, a lavish Hollywood Hills villa, and ethereal conversation that drifts as lazily as they do in their oversized pool. When Clarke arrives on the scene, the narrative splits into a double track. One involves Clarke taking several meetings with studio executives about the financial requirements of the film we’ve already been watching, and the other is, to use an anachronistic term coined by Quentin Tarantino, a “hangout” film where the lovers and Clarke watch a lot of television and re-enact what they’re seeing, sometimes straight into the camera. But the breaking of the fourth wall is only the tip of the iceberg in the movie’s blatant exposure of the process itself. The set-up alone is metacinematically dizzying, because we see the actors interact with each other, the space and the camera well before Clarke has arrived in Los Angeles. In only the second scene, we can hear Varda’s crew say, “Sound rolling. Camera rolling. Action.”

This self-reflexive acknowledgement of the filmmaking process effectively means there are at least four layers of reality. The film follows Peter Wollen’s framing of “counter-cinema” quite clearly. It is a film with multiple diegesis and an emphasis on the false binary of reality versus fiction, though it also doesn’t purport to tell us what is the distinction between those two. The first “reality” is within the fiction itself, a struggle of a vigorously independent Shirley Clarke on a mission to garner financing for a Hollywood movie. The second reality is Agnès Varda filming Clarke’s exploits, which, again, has been acknowledged multiple times, not just with the crew but in actual dialogue from Clarke herself and in multiple instances of Varda clearly being seen in the reflection of a mirror. The third layer is the film that Clarke has made - which further complicates the funky temporality of the entire enterprise in a fashion not unlike Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1962). And the fourth is the dissolution of fiction and documentary binaries as all five actors (the love triangle, Clarke and Varda) play themselves.

Playing oneself seems to open up a world of Sartrean self-questioning, an ontological debate about the nature of being in the context of acting, a solipsistic existentialism which happens within the opening credits. Both Varda and Kiarostami were fond of using the credit sequence as a mise-en-abyme to prime the pump, as it were, for the philosophical question at the forthcoming film, and here, for Varda, that manifests in a scrolling card which lists the names of the cast and crew while the three protagonists say in a dithyrambic, spiritual incantation:

We are stars. Can we be actors and be real? Can we be real and be in love? Can we be in love and be actors? Can we be in love and be real? Can we be real-life true live actors? Can we be like Cole Porter’s “True Love?”

They then launch into the Porter song as a unit, until Ragni says, “Agnès will cut this because you have to pay royalties.” These vaguely comical questions belie a larger metacinematic internal debate about their own authenticity, and whether such a thing is even possible considering their celebrity status. These questions get asked throughout; it is a repetitious touchstone, as if all three actors can’t realize themselves in an age of constant publicity. To make matters even stranger, the direct address to Varda off-camera implicates the director as inherently inauthentic. Even though this is a film within a film (in spite of Varda’s own protestation to that) she is not the director of the film within the film! Clarke is, though we haven’t seen her yet.

Lions Love is perhaps most notable, however, for the mirroring of Varda and her American equal. She makes Clarke go through a narrative arc that mimics her own brief struggle with Hollywood producers (even providing a couple moments of color commentary from behind the camera), but the most confounding moment happens near the end when all lines of fiction, such that they still exist, are completely broken. In a moment where Clarke is supposed to overdose on unmarked pills, the actor/director suddenly speaks directly to Varda by pleading, “I just can’t do it, Agnès. I’m sorry. I’m not an actress… And I certainly wouldn’t kill myself about not being able to make any goddamn movie.” Varda, still behind the camera, pleads to her cameraman not to cut despite the interruption, so there’s a funny consideration of whether or not this is on purpose, all of which is accentuated by Varda replacing Clarke immediately, inexplicably wearing the same costume.

The self-referentialism in Lions Love isn’t just a formal tick for Varda, it’s the film itself. Varda, an outsider to Los Angeles, takes an ethnographic approach to her California films that becomes not just a reflection of her own journey, but especially of Los Angeles which she paints as a self-mythologizing sun-drenched madhouse and bastion of hippie sexuality. The seemingly insouciant treatment of layers of reality and fiction, reified by the presence and invocation of American counterculture and hippie lifestyles, obfuscates the rigorous formal treatment to her subject: a reflection on the hypocrisy of celebrity culture and the overwhelming influence of network television and the news. Alison Smith explains that the "dialectic exchange of influence between public and private” was typical of Post-1968 intellectualism in France, and in fact the only moment of real sobriety in the film happens as the trio watch television coverage of Robert Kennedy’s assassination. The decision to cast these specific avant-garde celebrities as themselves, using herself as a (mostly) off-camera presence, mirrors the incongruity and social tumult that was prevalent during the late sixties. Varda was abroad in California while most of her filmmaking comrades were in Paris during the mass protests in May of 1968, so the reception of something as traumatic as Robert Kennedy’s death is portrayed in Lions Love as distanced as the Brechtian use of self-reflexivity.

The implication of the filmmaking process is similarly considered by Abbas Kiarostami in the series of films now colloquially known as “The Koker Trilogy.” Though the films aren’t conventionally linked in story, they nonetheless ripple off each other like stones thrown across a lake. It goes like this: In 1987, Kiarostami releases Where is The Friend’s House?, which catapults him into international recognition. The film, typical of the first Iranian New Wave which presented as heavily influenced by Italian Neo-Realism, catalogs the journey of a young boy who is seeking out a classmate in another village because he has accidentally taken his workbook home. Then, in 1990, the Manjii-Rudbar earthquake killed somewhere between 35-45,000 people and, Kiarostami, wondering if his two former co-stars were still alive, tells his producer about his concern, which then becomes the semi-fictional And Life Goes On (1992), where an unnamed director (Farhad Kheradmand), clearly acting as a proxy for Kiarostami, drives to Koker and searches for the young boys who starred in his previous film. In that film, The Director (as he is surreptitiously credited) talks to a young man who has, in spite of the earthquake having killed some sixty members of his family, gotten newly married not five days prior. The trilogy then concludes with an exploration of that one scene, blown-up like a large scale photograph, in Through the Olive Trees (1992), where Mohammad Ali Keshavarz plays a director (but with his own name, yet standing in again for Kiarostami), making a film about which we don’t quite know, but which centers the love story we had seen in the film prior.

Through the Olive Trees begins with Keshavarz announcing his role as the director directly to the camera, in a similar manner to Varda’s The Beaches of Agnès (2008). Though the latter is a documentary, the opening line by Varda casts a pallor of metaphysical playfulness. Just as Lions Love contains within it a multi-layered, serpentine version of reality and fiction, Through the Olive Trees’ self-reflexivity flips constantly between the fiction itself and our omniscient view of the entire enterprise. There is the behind-the-scenes “documentary” of Keshavarz’s film, the fictional narrative of the film itself, and the revelation later of the film-within-the-film that Keshavarz is filming that was seen previously in And Life Goes On.

Keshavarz is there to cast a local actress for his film, so he goes around a swarm of young girls asking their names and where they’re from. All of the locals are using their real names, so their existence penetrates the typical walls we assume exist for fiction - of which this is one. Except that the fiction we are first presented with is actually a pseudo behind-the-scenes documentary, or at least that is what seems to be announced by Keshavarz’s self-acknowledgement as a director within the film. But this framework is almost immediately subverted in the following scene as a faceless woman picks up an actor off the side of the road who had appeared in Where is the Friend’s House? What fiction is this? She asks him if he’s been able to procure chalk for the film’s slate, to which he asks, is that “like what I saw in Where is the Friend’s House?” Thus Kiarostami self-reflexively illuminates not just his own involvement and career, but the apparatuses of filmmaking itself, punctuated by the man asking Mrs. Shiva if he can have a role in the film. But what film? Through the Olive Trees? Or is it Keshavarz’s film? Is there a difference? Does it matter?

What much of this plays at, between both Varda and Kiarostami, is a direct contradiction of David Bordwell’s theories around cinematic continuity. Bordwell’s 1985 study on editing was centered on the classic Hollywood tradition of obscuring the apparatus to create a sense of harmony and thus perpetuate the fiction that what’s happening on screen is real. But Varda and Kiarostami both swing the Brechtian pendulum as far as it can plausibly go in the opposite direction in a counterintuitive attempt at a “deeper truth,” or, as Kiarostami himself said, “The most important thing is how we make use of a string of lies to arrive at a greater truth. Lives which are not real, but which are true in some way.” Though Kiarostami and Varda’s films, at least before the advent of the digital camera, adhere to a fairly strict Bazinian realism, they also make use of several Brechtian principles of self-reflexivity, particularly the “rejection of voyeurism and the fourth-wall convention.”

Through the Olive Trees is, however, not quite as simple as a self-reflexive meditation on the films that precede it, as actors and scenarios change ever so slightly. Though the house being filmed at and the main players are the same, the costumes have been altered in barely noticeable details - in this case the dress the young woman wears. Like a game of telephone, the further away we get from the source, the flimsier our grasp is on the story’s authenticity. The house, for example, does not actually belong to the old woman who “lives” there now; Kiarostami himself mentions this himself, but we’ve also seen it occupied by another actor in And Life Goes On. So the insistence on material reality is barely consistent. The sense of realism always remains the same, but because this is clearly not their house we get a stranger, more complex take on what “truth” is. Adding to this complexity is the presence of Ahmad and Babak from Where is the Friend’s House? who sit behind the crew to watch the filming take place - except no one, least of all Keshavarz as Kiarostami, acknowledges their presence.

Kiarostami continues to call out the artifice of filmmaking when filming finally begins on the scene we’ve seen in the previous film. The Director, still played by Farhad Kheradmand as in And Life Goes On, appears on screen and thus reveals the preceding film even further as a fiction. Now here, he must act against a young man who can’t say his lines because of a stammer and must be recast. When he finally is, Hossein (Hossein Rezai) and The Director go through an endless amount of takes in a lightly comic behind-the-scenes sequence reminiscent of François Truffaut’s Day for Night (1973). This seemingly banal re-casting illustrates a larger modus operandi for Kiarostami in that it deliberately calls out the inherent artificiality of filmmaking by telling us this is the actor’s real house while clearly casting someone foreign to the area. In this sense the “deeper truth” can only be achieved through the use of another actor because, pragmatically, the actor that “does” live there cannot speak in front of others without a debilitating stutter. Instead, a different truth altogether is brought to the fore, which is that Hossein’s real, off-camera romantic troubles with the young woman playing his wife has been recreated by Kiarostami for his own purposes. It is also a subversion of his own film because the young couple’s union in the face of incalculable loss is presented as a facsimile for Koker’s fortitude in And Life Goes On, while in Through the Olive Trees it is the main inhibitory factor preventing Keshavarz’s film from being a smooth operation.

Hossein has trouble getting his lines right, and, in between these repetitive acting mistakes by both him and The Director are small interactions between Keshavarz and his skeleton crew, amongst which is fellow Iranian New Wave director Jafar Panahi playing himself, but Kiarostami is only just beginning to peel back layers of perceptive reality. In the following segment, we witness a particularly strange temporal shift, as Keshavarz drives Hossein to the site of the memory he’s previously relayed. Now reliving it for the camera, Hossein chases after his paramour’s grandmother to beg for permission to marry. But we then hear a crew member yell “cut,” and the reveal is that it’s not Keshavarz’s set, it’s Kiarostami’s set, as he’s briefly seen through the olive trees, like Varda in the reflection of a mirror. So all of this action with Hossein, we’re led to believe, was happening just beyond the scenes of And Life Goes On. This head-scratching moment, in which Kiarostami, Keshavarz and The Director are all visible with multiple camera crews, raises yet another possibility. Keshavarz is not a stand-in for Kiarostami but rather another director entirely, who is shooting his own film which resembles Kiarostami’s work and which happens to use certain actors and elements of the real-life person.

Kiarostami himself was very ambivalent about “reality versus fiction,” but whatever the case the film only moderately touches on these various segmentations afterwards. Instead, in the middle of the film, Kiarostami presents a sort of thesis scene for the Koker Trilogy. As Keshavarz goes on a morning stroll with The Director near cast and crew camp, he tells Farhad he can communicate with the souls of the valley but he must do it loudly so they can hear. He does, laughs and says it's just an echo. The film itself, an echo in a valley of physical and spiritual devastation, becomes a reflection to this conversation about death and the lastingness of lost souls. What’s ultimately so fascinating about the entire film is that it has these markers of the audience’s base reality (mentions of Kiarostami’s previous films, actors playing themselves or roles they’ve played before, Jafar Panahi playing himself which is especially anchored in our timeline, as he is the AD for Kiarostami), but then trickles out into an ever-expanding universe of artificiality that pulls further and further away from itself, like a vast expanse of unexplored and constantly expanding space.

In a live interview conducted by film programmer Peter Scarlet in 2015, Kiarostami expresses a wish that conversations around his films would go beyond cinema, directing and acting. In other words, who cares if it’s “real” or not? Similarly to Varda in Lions Love, Kiarostami isn't self-referential for self-referentiality’s sake. In fact this was expressly not his intention, because he didn’t want to “repeat” himself with what he had done in Close-Up (1990), but instead simply wanted to tell the fuller love story from And Life Goes On and believed this method to be “the best way.” But even if deliberate self-referentiality was not Kiarostami’s intention, one film becomes the “fictional motif for the next” in a constant, pendulum-like overarching apparatus that swings between documentary and fiction.

As Jamsheed Akrami suggests, Close-Up and Through the Olive Trees mark turning points where Kiarostami goes from using cinema to reproduce reality to using cinema to manipulate reality. And this intention to do so is aided tremendously for both Varda and Kiarostami with the advent of the digital camera. The former first used it as a reawakening tool in the revelatory The Gleaners and I (2000), while the latter did in a total upending of his own fiction at the end of the Palme D’Or winning Taste of Cherry (1997). For Varda, as she explains within her documentary, the camera’s “effects are stroboscopic, narcissistic, even hyperrealistic.” It allows her to capture (and keep) happy little accidents, like a moment when she forgot her camera was on and thus inadvertently films the lens cap doing a little dance, which she then scores to a jaunty tune. This moment is oddly similar to Kiarostami’s ending of 10 on Ten (2004), a paratextual documentary to Ten (2002), in which the director lets his digital camcorder dangle towards a pile of ants. Varda links digital cinema with new horizons in finding absences, as well as herself. She discusses filming her left hand with her right hand, and plays games while driving in the car and using her right hand to “capture” semi-trucks. Meanwhile, Kiarostami took a camcorder on a research trip in Uganda for his first film outside of Iran, the sober ABC Africa (2001), in which a plenitude of incidental footage became the documentary itself, including seemingly mundane conversations over the music playing in a taxi or a rash of school children dancing in an alley. While there isn’t anything necessarily here that relies on the camcorder that Varda or Kiarostami could not have done with 16mm or 35mm cameras, it is the possibility that anything can be filmed and hard choices need not be made. For both Varda and Kiarostami, digital cinema meant the realization of a long-held maxim that everything is cinema, or, as Varda says at the end of The Beaches of Agnès: “cinema is my home. It’s where I’ve always lived.”

Digital cinema also seemed to allow both filmmakers to work even more independently. In the same self-reflexive documentary, Kiarostami says that, “this camera allows artists to work alone again” and, thanks to this creative independence, it is “an invitation to new discoveries” and experimentation “free from capital.” In the similarly meditative behind-the-scenes Around Five (2005), Kiarostami explains about his process that he would switch his camera on and “go to sleep.” Varda meanwhile agrees in her final film Varda by Agnès (2019) that the digital camera meant a divestment from traditional crews and thus a freeing of the fear of “intimidating the subjects” of her documentaries. The point for both seems to be the removal of the artist from the process, turning themselves into active spectators in much the same way Kiarostami suggests the audience fills in the gaps of the narrative. The question seems to be: how much can we let nature speak for itself? Following Robert Stam’s suggestion that “it is a mistake, first of all, to regard reflexivity and realism as necessarily antithetical terms” and Jonathan Sterne’s argument that “[higher] definition is not realism, and realism is not reality,” we might consider how Varda and Kiarostami’s use of the digital camera doesn’t replicate realism more forcefully than it had before but does allow them to film more, and thus a wider breadth of reality.

This desire to strip down the filmmaking process so that subjects and themes appear to represent themselves is counterintuitively realized by both through a massive interlocking system of interpolating mechanisms. Varda explained this process early on as cinécriture, a portmanteau of cinema and écriture (writing) that effectively categorizes herself as an all-seeing, all-controlling artist. As Robert Stam explains,

In the postwar period in France, both film and literary discourse came to gravitate around such concepts as ‘authorship,’ ‘écriture,’ and ‘textuality.’ The New wave directors’ fondness for the scriptural metaphor was scarcely surprising, given that many of them began as film journalists who saw writing articles and making films as simply two variant forms of expression.” (p. 6)

While Kiarostami did not coin a word to describe his status as auteur, he did, apparently without much previous knowledge of European cinema or the notion of the camera-stylo that Alexandre Astruc first referenced, say that, for him, “the camera is exactly the same as a pen. It can be used by a common person or it can be used by Baudelaire to create a great poem.” Kiarostami’s invocation of the French poet and essayist further reminds oneself of Walter Benjamin’s observations on Proust’s theory of mémoire involontaire, in which the “former concludes that ‘the past’ is somewhere beyond the reach of the intellect and unmistakably present in some material object.” That material object, in this case, is the photograph.

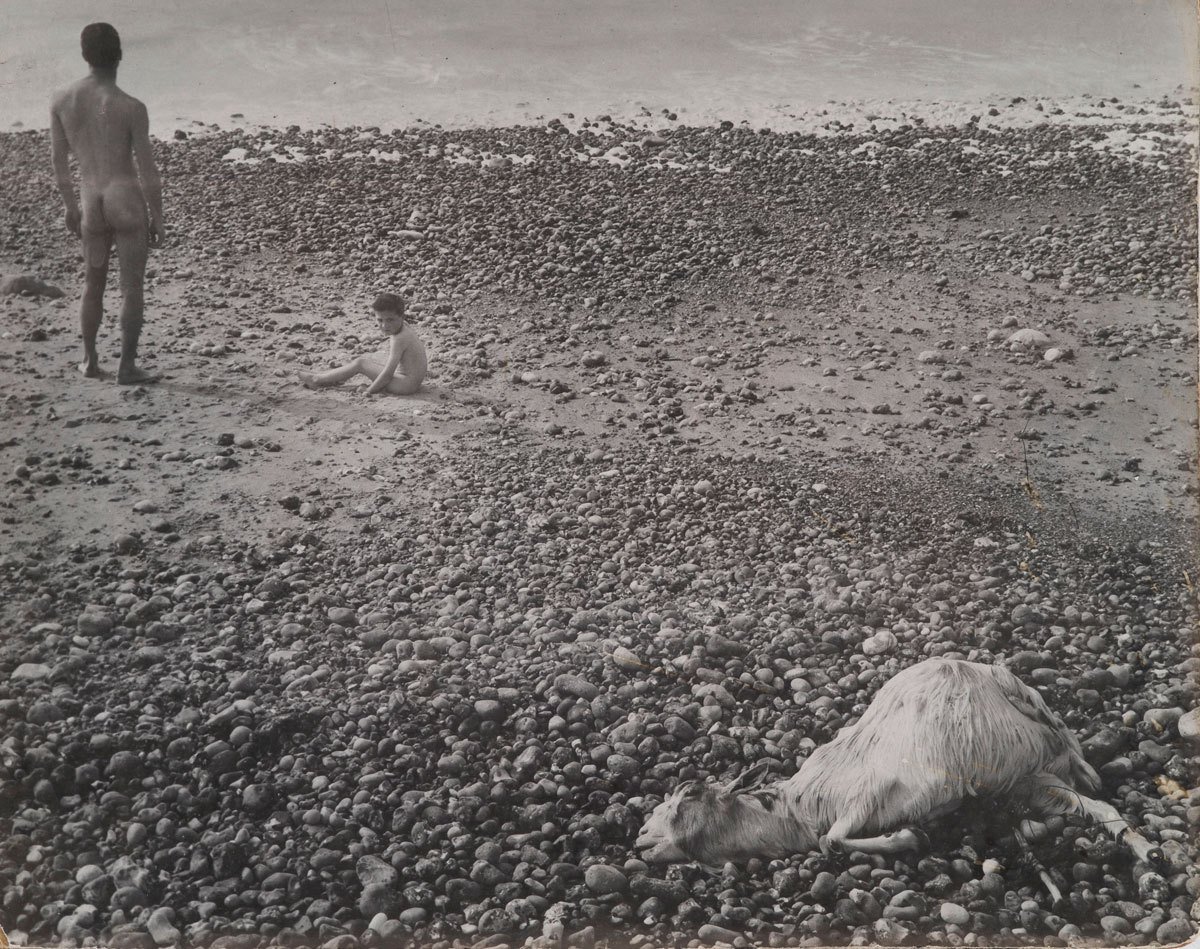

Both Varda and Kiarostami came to filmmaking without any previous cinephilia and instead, in its place, a deep reserve of appreciation for photography. For Varda this photographic preference is constantly imbricated on her cinema instead of incorporated within it, creating a filmmaking style that resembles a graphic tableau. Both filmmakers were expressly intrigued in the photograph as a material object of memory whose status as a document of historical fixity should be inherently questioned. Varda summed up this artistic credo in Varda by Agnès in a reflection on her installation Quelques veuves de Noirmoutier (2006, created for Fondation Cartier in Paris) by asking, “What happened before and after a snapshot was taken? Or in a film, what happens when they exit the frame?” This same consideration became Abbas Kiarostami’s final, posthumously released film, 24 Frames (2017), in which the artist partially animated twenty-four photographs to imagine the minimalist action that might’ve taken place on either side of its fixed place in history. Both artists seem to be following Michel de Montaigne’s philosophy of the self, which “can be summed up by the phrase ‘que sais-je’ (What do I know?), which reveals that any investigation of society is concomitantly an investigation of one’s own relationship to that society.” For Varda this consideration is most profoundly felt in the short documentary, Ulysse (1983), in which she implores herself and the subjects of a photograph she took some thirty years prior to remember their involvement.